SYLLABUS SPRING 2021

|

My favorite course to teach starts now! Here's my syllabus for my graduate seminar in professional development and career planning.

SYLLABUS SPRING 2021

0 Comments

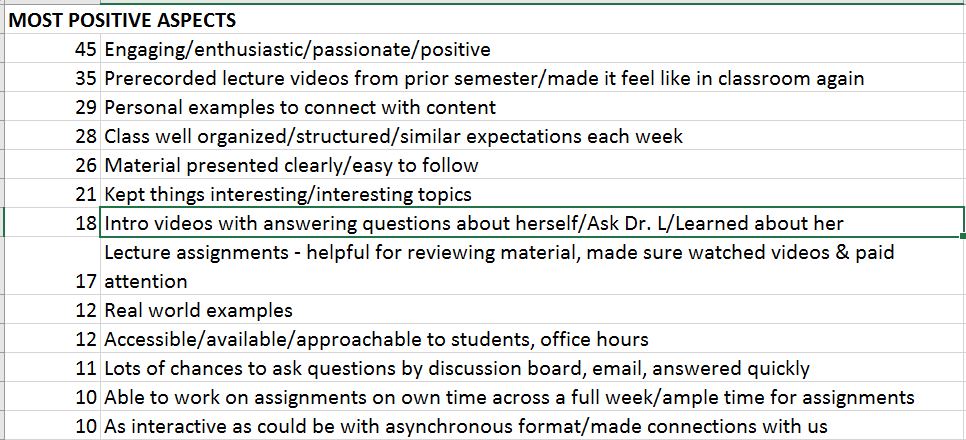

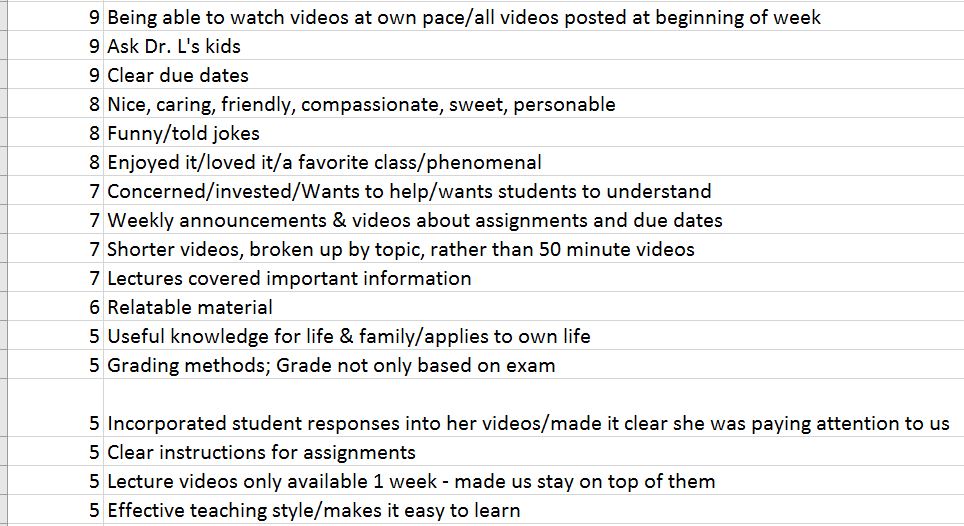

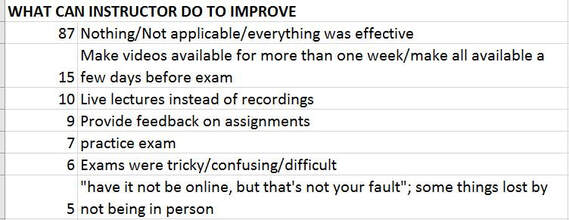

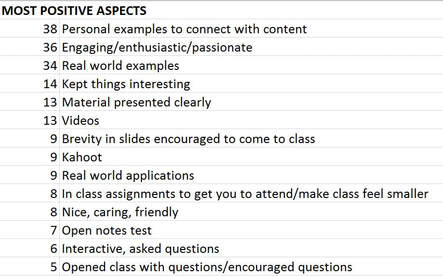

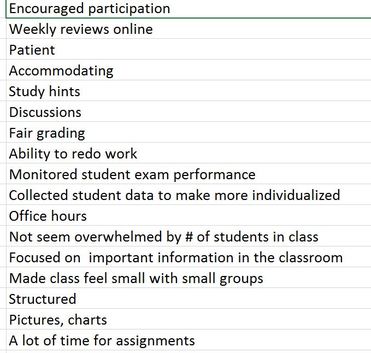

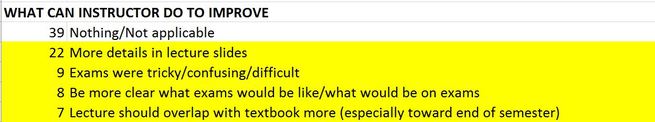

This Fall, I taught a 344 student general education course on individual and family development across the lifespan. You can see my syllabus here. Today, at great personal cost to my self-esteem, I read and summarized all written responses from 266 students (78% response rate). How did I summarize? Learn more about my technique, and why. I am going to share the summary of every single response with you. Then, I’m going to summarize differences between perceived strengths and weaknesses of this semester compared to Fall 2018 in person. Then, I’m going to share what these ratings (granted, just one class) can tell us about how to support students’ online learning in large classes. I share this information because it was hard for me to find in Summer 2020. Our university does an excellent job in preparing online instructors, and offered many additional trainings and workshops for faculty to take their classes online. But our online classes are historically designed to be relatively small, and so some of the best practices do not easily scale to large format classes. I consulted with Suzanne LaFleur, Director of Facuty Development at UConn’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, who helped me talk through ideas and provided some great advice that I incorporated. It’s important to note that the way I structured the course only worked because I had substantial TA support. Communication and grading with 350 students would have been impossible if I did not have that kind of support. You can find the full summary of every single positive comment and suggestion for change here. Here are the most common responses, noted by 10 or more students, to the question, “What was the most positive aspect of the way in which this instructor taught this course?” Here are the next most common responses answered by 5-10 students: Here are the most common responses, noted by 5 or more students, to the question, “What can this instructor do to improve teaching effectiveness in the classroom?” (ha – just realized the “in the classroom” part): Interestingly, many of the most positive aspects of the course remained consistent – being engaging/passionate, using personal examples and real world examples, presenting clearly, being nice/caring/friendly, funny/told jokes. Areas for improvement they mentioned in 2018 but less so in 2020: In 2018 many students requested more details on the slides; only 3 mentioned this topic in 2020. More 2018 students described the exams as tricky, though still some did in 2020.

Here are some lessons for online teaching that I take away based on the SETs:

If you are teaching a large online course this Spring, good luck! Feel free to share suggested of what has/has not worked well for you. “What my Fall 2020 teaching evaluations tell us about teaching large online classes first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on January 10, 2021.” * La-de-da. Let’s pretend we didn’t notice how long it’s been since I last posted.

Here is my syllabus for Fall, 2020 in HDFS 1070, a general education lifespan class on individual and family development. The course was fully remote. Here is my syllabus from Fall 2019, fully in person. Here are the things I changed/adjusted to be fully remote:

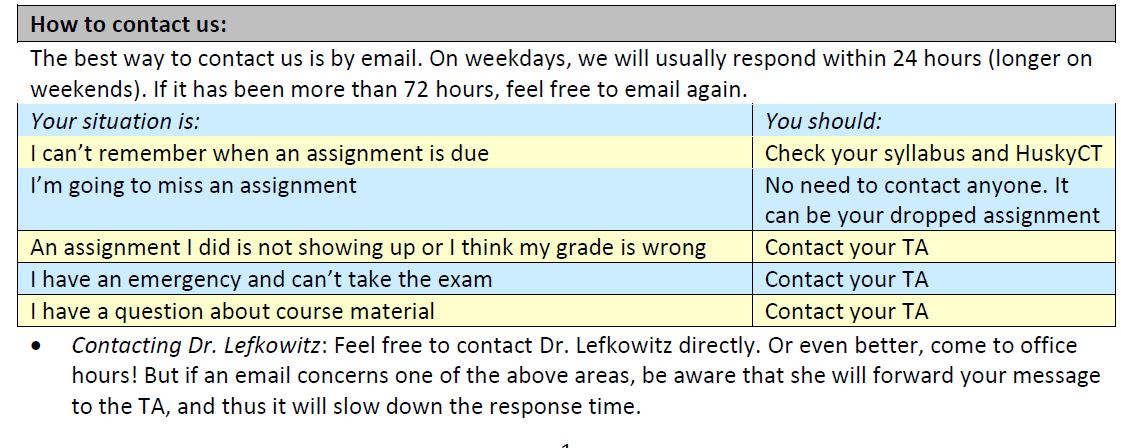

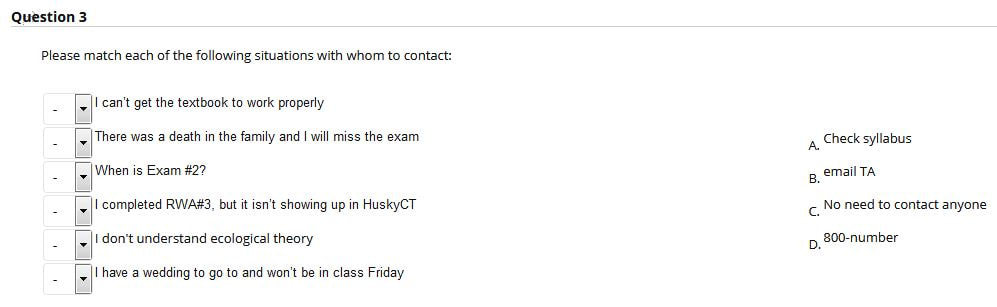

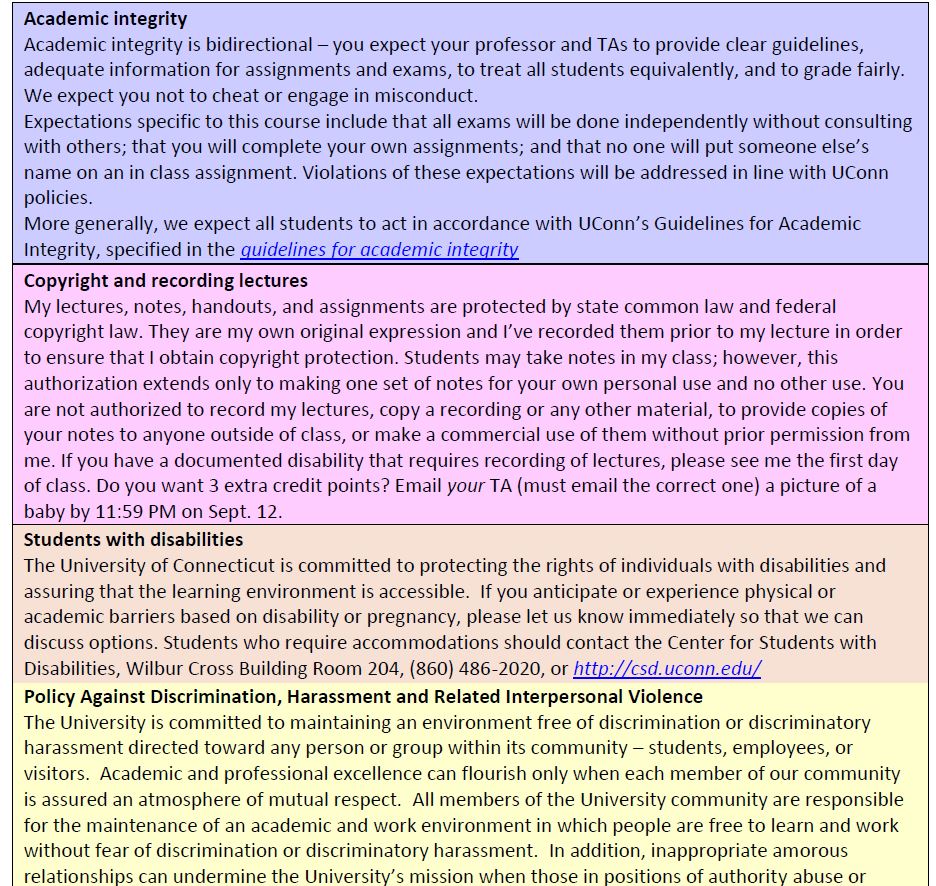

“Introductory Individual and Family Development: Remote, large section class syllabus first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on January 5, 2021.” The last two academic years I taught a large intro course, with 300 and 350 students. The last time I taught a course with 200 students was my first year as an assistant professor – 1998. The last time I had 100 students was 2000. So, I had some new learning to do about how to handle large classes, and also, how to teach large classes in 2019 (well, technically it was 2018). One large management issue with 350 students is emails. I was fortunate to have three TAs each time I taught, so they honestly dealt with the majority of the emails. Even if students emailed me, I would skim the email and assuming it was one that should go to the TA, forward it to that student’s TA (they each had part of the alphabet). How should students know if they should email me or the TA? It’s in the syllabus, of course: This information was my attempt to decrease overall emails and make it as easy as possible for students to know whom to email and when. It’s a challenge in a large course to appear both approachable when needed and not standoffish, but also not have every student email weekly with questions they could answer on their own. Despite these attempts, I received emails from students every single day, at least 90% of the time about topics they should have emailed their TAs (or no one) about. The TAs became very good at screenshotting the syllabus and sending it to students in their replies. Unfortunately, a clear syllabus is not very useful unless students read it. And, it has become very challenging to get students to read the syllabus. There is little incentive, as far as I can tell, especially given how little effort it takes to email the instructor/TA with a question rather than look for the answer in the syllabus. I tried to keep my syllabus as short as possible – it is five pages. Perhaps that seems long, and I have read about the one page syllabus, but note that the one-page syllabus usually has a number of appendices or addendums, at which point you are asking students to read multiple documents. I’d rather have it all in one place. I use bullet points and tables. And multiple colors. Yes, I have a syllabus quiz. It is due one day after the end of add/drop period so that everyone in the course can take it. It is worth points toward their final grade. It is online so they can take it at home, with the syllabus in front of them. They can take it as many times as they would like until they get a score they are satisfied with. Most students did eventually get 100% (84% of them). But 4% never took it, and 8% scored 83% or lower, even with retakes. The most recent time I taught the course, I also put an Easter egg in my syllabus. Any guesses on what percent of the class did the extra credit based on the Easter egg in the syllabus? I’ll wait. 11%. You might wonder, why would I reveal my Easter egg in a blog post? I figure if the students didn’t find it in the actual syllabus for the course they took, they are not going to find it buried in a blog post.

Want to see my whole syllabus? You can find it here. Normally my blog posts provide advice for academia. I’m not sure this post could serve as best practices for getting students to read the syllabus, though, because, as you can see, I have not been particularly successful. I would love to hear what you have done to get students in large classes (any classes?) to read your syllabus. “It’s in the syllabus first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on June 20, 2019.” HDFS Graduate seminar in professional and career development

My grad seminar on professional and career development may be my favorite course to teach (I had to temper this statement a bit this year, as two of my students this semester TAed for me in my general education lifespan class, where I told 350 students that class was my favorite to teach). But perhaps my favorite position to date was director of the graduate program, and one of the most fulfilling aspects of my 20+ years as a professor is mentoring graduate students. Teaching this course feels like mentoring more than teaching. My learning objectives have not changed much since I previously taught this course. However, I have updated the readings, played with the order of topics (there is often a chicken/egg issue of whether to cover, for instance, “how to” related to publishing and peer review, or ethics of publishing and peer review, first), and added one new assignment. Here is the full syllabus: syllabus_5095_2019-sp.pdf “HDFS Graduate seminar in professional and career development first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on January 31, 2019.” How Zumba made me a better teacher

Karen Kelsky describes how Zumba is an amazing release for her. In Karen’s words, “Dance has given me back to myself. It’s endorphin-pumping fun, it’s exercise, it keeps me fit, it lifts my depression, and opens up my heart.” Spoiler alert: This post is not about how much I love Zumba. Or how it lifts my depression or serves as a release for me. Instead, it’s about how my ineptitude at Zumba helped me understand my students better. Before I describe my ineptitude at Zumba, however, it’s important to note that I completely agree with Karen that everyone should find their own thing whether it’s “running, or art, or music, or yoga, or knitting, or walking, or meditation or a hundred other possibilities.” For me, right now, it’s yoga and barre class, and reading/listening to fiction, and Rubik’s cubes. I have always been a straight A student. How often do I say this? Do I sound like the annoying brainy girl at the desk next to you in math class? I know I say it a lot, but I think it explains aspects of my personality. I don’t think I’m unique here – I know a lot of people in academia can relate. So many PhD students and faculty have similar experiences/personalities. It’s a trait I carry with me into my job. Years ago when I was put in charge of an assessment plan for our department’s undergraduate program, and the previously submitted version received marks of “acceptable,” I immediately launched a 3-pronged approach to assessment to bring us up to “exemplary.” When I do my IRB online quizzes I tend to get 100% on each module (and if I don’t, I’m annoyed). When my son mastered solving the Rubik’s cube, I had to learn how to solve it. And then he mastered the 4X4, and subsequently, so did I. We figured out the 5X5 together. So, I am generally highly motivated to do well, and I generally feel as though if someone teaches me something, I can learn it. But then I took Zumba. I mostly could learn the steps and follow along. But, what I couldn’t do, is look good doing them. I would watch the instructor – who was excellent – and I would try to do the same moves, and they were… not excellent. If you look at the videos in Karen Kelsky’s post – I looked nothing like her. I looked like an uncoordinated 40-something woman trying to do Zumba. Or just like brainy 15-year-old Eva trying to stand in a circle at the school dance with her friends and awkwardly move to the music. Most strikingly, there was an upper body move (which, after much googling, I’ve discovered is called the Reggaeton pump) that looked very cool on the instructor, and very ridiculous on me. No matter how I tried, I could not master that move, even though I felt I was mimicking the instructor. During a Zumba class, I had an a-ha moment. I have had meetings with students, where I am trying to explain a concept to them, that seems very straightforward and clear to me. Negative reinforcement comes to mind. And of course, I believe my explanation is very straightforward and clear. It often seemed like they were working hard in the course, but they still couldn’t do well on the exam, or clearly explain concepts in their paper. And finally, I realized what they must feel like when I try to explain a concept to them. They just couldn’t get it, no matter how much I explained it or how straightforward it seemed to me. Like me and Zumba. It reminds me of Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. I know it’s controversial. I know that many researchers have demonstrated that different domains of intelligence are highly correlated, and believe that there is an underlying IQ driving these domains. I don’t dispute those claims. And yet, I also don’t dispute that most of us are not equally talented in every possible domain. That is, even if ability in these domains is generally correlated and linked to an underlying factor, we still may have differential ability across domains. There is no way that everyone is equally talented in every domain. And, we may be more teachable in one area than in another. This realization, this personal realization, definitely helped increase my compassion for students struggling with a concept. Sometimes faculty attribute students’ inability to comprehend to lack of effort. But we as instructors must also recognize that inability to comprehend doesn’t always indicate lack of effort. Sometimes, things that come easy to some of us take enormous effort for others. “How Zumba helped made me a better teacher first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on November 1, 2018.” *Side note: My blog had been rather neglected for the past 2 years. I always have good intentions, but they rarely translate to finding the time to write here. This summer, for whatever reason, I found the motivation to regularly open up my file of “future blog posts” and sit down and write them. In almost exactly three months (5/25 to today, 8/26), I wrote 42 posts, 27 posted for three months, twice a week, and another 15 scheduled to post through 10/16 (this one I’m writing right now for 10/18 makes 43). That’s a lot of writing time, and one might argue that I could have written one or more manuscripts in the time I spent writing blog posts. But it’s debatable whether I would have used the time as effectively if it was manuscript-focused time. And, at some point in your career, you can take a bit more freedom to make choices, such as being generative in different areas than the traditional ones. I recognize, though, that I cannot write nearly as frequently during the academic year. So, perhaps my posts will continue beyond mid-October, but if there’s another hiatus, thanks for coming along for the ride and I hope you found something useful. And now, student evaluations of teaching. I will refer to them as SETs which is what they are called at UConn. The first time I received student evaluations of my teaching I was a graduate student TA for a section of research methods. I called a friend and told her I was sad because I had a really negative review. She said, really, I had great reviews! And after we talked for a while, we figured out that both of us had mostly positive feedback with 1-2 negative people in the pile, it was just that I perseverated on the negative one and couldn’t remember the positive ones, and she ignored the negative and focused on the positive. I still find it hard not to perseverate on negative feedback in my SETs. I think it’s because the most negative ones are generally the most strongly emotionally valenced, and so they are the most memorable. At least to me. I really want to take student evaluations into account when I revise my course each year. But I find that if I’m not careful, those highly emotionally valenced ones may sway my view. I have even at times changed a course in response to such a review, having then the next year more students complain about the new format. SETs don’t have the same meaning for me now that I am post-tenure, post-full professor. Previously it at times felt like SETs were linked to job security. Now, to be honest, as long as I don’t get scores low enough to raise eyebrows in the Provost’s Office, no one is going to care much about my SETs. All that said, I do want to learn what students did and didn’t like about my courses, and figure out how to improve them. I had a colleague who prided himself on never looking at his teaching evaluations. I’ve had other colleagues who, when I was Undergrad Director and met with them to discuss lower ratings, would blame it all on the students, such as, “this was such a bad bunch this semester.” I can’t quite understand that. I don’t think we should bend over backwards to please students all the time, but I do think we need to consider students’ perspective on the course. When I was Undergrad Program Director, I often had to help other faculty interpret their SETSs and figure out how to respond to them in course design. During this process, I developed a way to summarize the SETs for others, and I now use that technique with my own SETs. If you teach a small graduate course, you may find this technique less useful. But if you have a large course like mine, then summarizing them may help you find patterns. Essentially what I am doing is coding the responses. I pull up the open-ended responses, open an Excel file, and read through them one at a time. For each one, I try to code or categorize any unique point that person says. I keep a running tally of each point, so that the second time someone says “she was so enthusiastic!” I don’t make a new line, I just add a count to the line “enthusiastic/energetic/engaging.” I do separate summaries for “Most positive aspects” and “What can instructor do to change.” Once I’m done coding, I sort them by # of responses in descending order, and I can much more easily see the patterns and get a sense of the overall student perspective, rather than only remembering the most strongly worded ones. This year, when I first received my SETs for my 290 student class at the end of the semester, I skimmed them but didn’t take the time to read them. The sense I came away with from them was that they overall liked me and thought I was enthusiastic, but that students also were unhappy that I made them do group assignments because the class was a mix of freshmen – seniors; unhappy that instructor seemed unsure of herself; and unhappy that I relied on my notes too much. But when I tabulated, those last three points were literally each from one person – in a class of 290. That’s what I remembered the most, though. So instead, when I tabulated them, I could much more easily see the trends. Here are all of the answers to the question about “most positive aspects” that 5 or more students made: `So I get a clear sense that students like that I gave lots of personal examples, and real world examples, and students found me engaging/enthusiastic/passionate. All of these positives even won out over showing videos, so I take that as a strong win. Toward the bottom I can see the things that only one student mentioned as a positive: These are things that might make me feel good in some cases, but I don’t have to spend a lot of time thinking about them, either. Now, here are all of the things that 5 or more students said I could do to improve the course: I’m feeling quite good that the most common response was for students to say “nothing” or “N/A” or “I can’t think of anything.” After that, I’ve highlighted for myself the next most common things that students said. Lots of students would like me to have more detail in my notes. That’s something that I’m not willing to change, because there is research on learning and memory to support my decision to have PP slides without a lot of detail, forcing students to pay attention and take better notes. In fact, 9 students said they liked the brevity in my slides. My best guess is that most of the students who asked for more detail in my slides were among the students who attended class infrequently, and they want me to post notes on Blackboard that have enough information that they didn’t miss anything. I’m not going to do that, but I can spend more time on the first day of class this semester explaining why my notes are the way they are.

Some students thought my (open-notes, open-book) exams were tricky. And some students thought I should be more clear about what exams would be like and what would be on exams. So I can probably spend more time in class pointing out some of the concepts that students find tricky, and talking about how to use the weekly review questions I post. A lot of the things I got out of this section of my SET’s are about ways I can help the students understand what is happening in the course, rather than changing my policies per se. But there definitely have been times that I have read something in my SET’s that has made me make some more radical changes in my course. This technique has really helped me take the emotion out of reading my SETs, so that I can concentrate on what students do and don’t appreciate about the course, and respond appropriately. How do you deal with student evaluations of teaching? “How to gather useful information from student evaluations of teaching first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on October 18, 2018.” A couple of years ago I wrote about whether you should do a post doc or not before looking for a more permanent job. Today I wanted to describe the different types of post docs that exist.

Let me start with a giant disclaimer, and one that I end up repeating a lot when we discuss these options in my professional development graduate seminar. If you are an international student looking for a post doc in the United States, your options are relatively limited, as you won’t be able to do an individual or institutional post doc funded by NIH (or a number of other governmental agencies). You cannot, unfortunately, be as picky in this situation. I always feel the need in class to say “I’m sorry” to international students as I discuss options more generally. Though since it’s not my fault, maybe I shouldn’t apologize… So, I would say at least in my discipline, there are five different types of post docs (I started with four but added a fifth as I was writing): 1. Institutional training grants. This category includes T31’s from National Institutes of Health, which are relatively common in my discipline. There are several advantages to institutional post docs. You do not have to plan for them a year in advance – you can apply on a regular application cycle (often late fall or early spring for a fall start date). They usually come with protected time for writing/getting your own research done. And, they usually come with a fair bit of professional development training – activities such as support for writing papers, support for writing and submitting grants, and support for going on the job market. When the PI’s apply to renew the T32, they usually have to report on the current status of all of their alumni, which makes the team of mentors highly invested in their post docs’ success. 2. Individual training grants. For these training grants, you apply to do a specific research project with a training program, and if you get funded, receive a stipend as well as some research funds to carry out the project. Generally, doing such a post doc involves a relatively involved application, and you have to identify a mentor before applying, often a year or more in advance. An obvious advantage of this type of post doc is that you’ve identified your own project and training – so, if you want additional skills in neuroscience/statistics/prevention/whatever, you can identify a specific team of mentors, training site, and research project to carry out that project. The disadvantage is that you have to apply so early, that you often have to identify the site and mentors up to two years in advance to be able to write the application so far in advance with the training team. In addition to F32 applications through NIH, some other common ones related to our discipline include: NSF SBE Postdoctoral Fellowship Spencer Postdoctoral Fellowship AAUW’s American Fellowship Fulbright (International project) Ford Foundation Fellowship Program 3. Individual fellowships outside of academia: I do not know of as many of these, but they would include things like the SRCD social policy fellows program, where you go to Washington DC and use developmental science to inform public policy in the congressional or executive branch. These are great for individuals who want to either find work outside of a university setting, or are interested in more translational research and want to get a sense of how to make an impact with that research. 4. Post doc position on specific research grant. Sometimes, faculty advertise for a postdoctoral position where they pay a full time PhD to work on a specific research grant. One advantage of such a position is it is generally an option for international scholars – that is, there aren’t the same citizenship restrictions. Another option is that if there is a specific researcher you want to work with, and if he has funding, it provides an opportunity to do so. The disadvantage is that, because you are paid off of a specific grant, you will be working on that grant and may have less freedom to work on other projects or to publish your work from earlier grad school projects. A lot depends on the PI you work for. In some cases, the PI really wants a project manager and you may end up doing a lot of participant recruitment, organization, running participants, and/or data management. In other cases, the PI really may need someone to analyze and write up data, so you may actually have an opportunity to build your CV and get publications out. It’s really important to get a very clear sense of what the PI will expect from you before you accept this type of position. 5. Teaching post doc. Some universities now have teaching post doc positions. These often require that you teach a certain number of courses for 1-2 years. Sometimes they also include dedicated time for your own research writing. For students who want a career as faculty at a smaller liberal arts college, but who are graduating without much teaching experience, such a post doc can be a good experience. However, you often also have to have a decent publication record to get the job. It’s rare that top liberal arts colleges will hire faculty without a publication record, even if they have a strong teaching record. So, think about your goals, and your record, as you decide what you need during this period before going on the academic job market. I haven’t even discussed all of the personal situations that might limit your options, particularly in terms of geographic mobility and partner issues. Basically, there is no one right type of postdoctoral position. It’s important to figure out both what your career goals are, what your constraints are, and what each specific post doc option looks like, and then find the best fit for you. “What type of post doc should you do? first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on August 9, 2018.” I started teaching in 1998 at 30 years old and with a 2 month old PhD. My first class was an introductory adolescent development class with 200 students. I was bright eyed and bushy tailed. They were not. I did not do well at engaging them in discussions. They did not do well on my exams. I tried to share my enthusiasm for research, but it rarely worked.

And at some point (10 years later, to be exact), I had been teaching for a decade. My undergraduate courses were relatively large, ranging from about 200 students in a general education course to about 60 students in an upper level advanced adolescent development course. I was around 40 years old, and I was already jaded on teaching, with decades left in my teaching career. At that point, my jaded self would go into the first day of class with almost a me-against-them mentality, waiting for them to be too demanding or too whiny or for me to disappoint them somehow. They annoyed me. I prepared for revolts. When they came up with excuses, I was intolerant and unbending. It was not a healthy way to approach teaching. In addition, it was not a good way to earn students’ respect or admiration. Looking back on it, I don’t even know that I’d now argue that my perspective was unwarranted. I had dealt with a whole lot of plagiarism, cheating, lying (e.g., I couldn’t come to campus because of a snowstorm in my home town, when a quick search demonstrated, 0 inches of snow in that town), disrespect (at the time, reading newspapers in class was the equivalent of being on one’s phone today), and generally bad attitude. I don't think I have many turning points in my life, but my teaching turning point was when my sister, 23 years my junior, started college. She was bright eyed and bushy tailed, though I imagine she doesn't appear that way in many classes. Sometimes one event can shake us up, and for me, Ryan starting college did it. That personal experience brought a whole new level of empathy to me as an instructor. Ryan was someone I knew and loved and respected. But she was also some who, I am sure, sometimes skipped class or handed in assignments late. She was, in many respects, a normal 18-year-old trying to figure out who she was, and to figure out the balance of using her transition to adulthood to learn things in the classroom while also having a social life, making friends, and sleeping among other things. Suddenly, my students weren’t a room full of young people out to game the system or get away with things. They were real people, with human faults just like the rest of us. I went in wanting to figure out how to inspire them. I wanted to teach them things they could use beyond my exams. I wanted to connect to them. I think as faculty we feel as though students don’t see us as real people. But, the same is often true in reverse. It’s easy for us to forget that students are real people too, just lots of them at once, each with their own competing demands for their time and attention. Just like us, they have competing demands, whether those demands are things we might think of as “worthy” like caring for a sick parent or working three jobs to pay for college, or not-so-worthy, like staying out too late partying or oversleeping. But whatever the reason, they are human. That semester, when my sister started college, I walked into the classroom with a whole new attitude. I didn’t walk in feeling it was me-against-them. I went in thinking about how they are each unique people with their own strengths and weaknesses and quirks. And I went in thinking about how they were people whose parents and siblings and other family members love them for the people they are. It completely flipped my attitude, and as a result, I believe, made me a better teacher. Even when a student emailed me about missing class, I tried to remember they were human, and sometimes humans oversleep. It doesn’t mean I automatically let the student make up the missed assignment, but I did try to have more empathy and compassion in my response. I still ask questions and sometimes am met with blank replies. I joke about how I need my water bottle for awkward silences. Once I jumped on a table and threatened to stay there until someone answered my question, reminding them how clumsy I am and that my life was in their hands. I still get frustrated at times, when they do worse on a quiz than I think they should, or when someone emails me the day before an assignment asking me basic questions that are answered in the assignment guidelines. I had a student who failed my class the prior semester because she never came (not even to the exams). I emailed her at the start of the next semester expressing my concern, and she came to most classes and earned a solid B. I know that another semester I had a student who wanted to miss the class on abuse in relationships because she didn't think she can handle it. Sometimes students miss classes due to health problems. One semester another student's grandmother died -- really died -- and given that she had lived with her, she had been busy with her role as executor of her estate (and debt). I sometimes see myself slipping back into my former perspective. Last semester I had 290 students in an intro, general education course. There was a lot of management of excuses and missed assignments, and by the end of the semester, I probably had less compassion than I should have. It helps me to remind myself that any of those students could be my sister – someone who really does want to learn in college, who genuinely is a “good” person (whatever that means), but just like any human, trips up at times along the way. So on the first day of class this Fall semester, I’ll try to walk in and feel love for all of these students, and hope I maintain some form of general positive will through the semester. “How I Became a Better Teacher When my Sister Started College first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on June 28, 2018.” I'm teaching my graduate seminar on adolescent development this semester. I teach it as a survey course, so lots of broad overview. I'm excited this semester because in addition to HDFS students, we have students from psychology, education, and nursing. Here's the syllabus: I love hearing the students' contemporary issues presentations. It really provides students an opportunity to delve into a topic of interest to them, and exposes all of us to the most recent research in a more controversial topic. I look forward to this year's presentations because the students chose different topics than the usual suspects. Here's the full list of topics: "The post Graduate seminar: Adolescent development" first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz's blog on January 14, 2016."

|

Eva S. Lefkowitz

I write about professional development issues (in HDFS and other areas), and occasionally sexuality research or other work-related topics. Looking for a fellowship?

List of HDFS relevant fellowships, scholarships, and grants Looking for an internship?

List of HDFS-relevant internships Looking for a job?

List of places to search for HDFS-relevant jobs Categories

All

Blogs I Read

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed