| lefkowitz_syllabus_5006_2022-sp_post.pdf |

|

I'm teaching my graduate seminar in professional and career development this semester, which is now officially a graduate course at UConn. You can find my syllabus here.

0 Comments

How do you find job ads?

In preparation for my Fall professional development graduate classes, I compiled a list of places to search for jobs, with some help from #AcademicTwitter. And because I never met a list that didn't look better in a spreadsheet, we made a spreadsheet of Places to Search for HDFS-relevant academic and alt-academic jobs. Behold: Places to Search for HDFS-relevant academic and alt-academic jobs It includes traditional places for faculty jobs, like Chronicle of Higher Ed and Academic Jobs Online. It includes some places the hip young people go, like the Psych Jobs Wiki (warning: Not for the faint of heart!). More specialized places like Obesity Society and Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management. And, places for primarily alt-ac jobs, like Idealist and the Versatile PhD. I'm always looking to add, so please send me suggestions. Want to check out my other compilation lists? Post docs (almost 140 listed) Fellowships (almost 100) Internships (almost 50) “Where to search for HDFS-relevant jobs" first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on May 14, 2021.” My favorite course to teach starts now! Here's my syllabus for my graduate seminar in professional development and career planning.

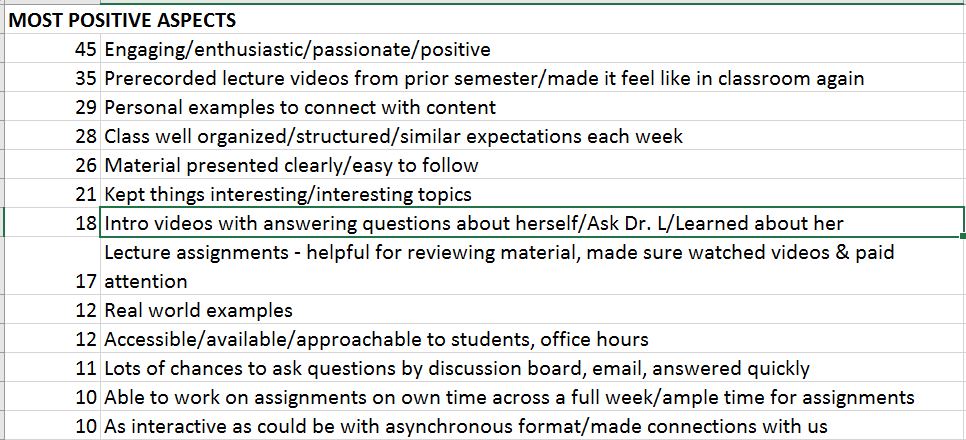

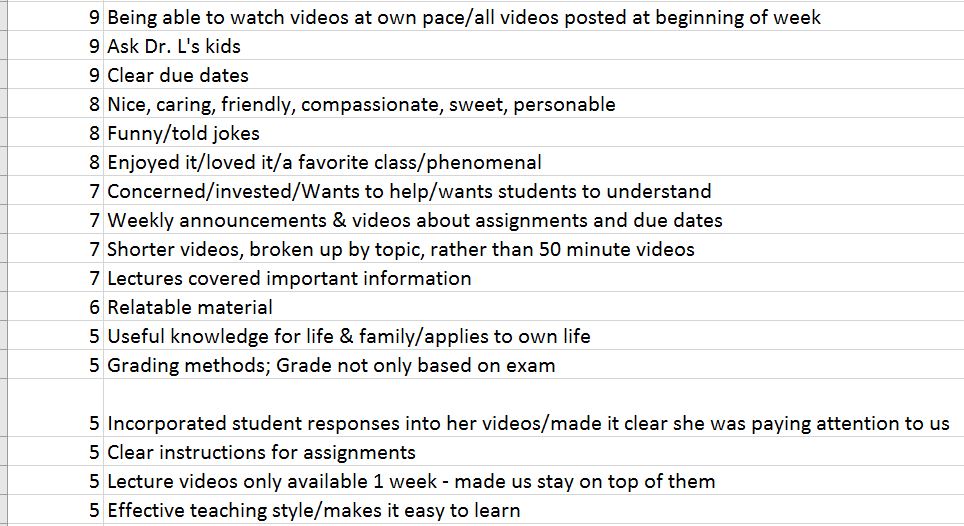

SYLLABUS SPRING 2021 This Fall, I taught a 344 student general education course on individual and family development across the lifespan. You can see my syllabus here. Today, at great personal cost to my self-esteem, I read and summarized all written responses from 266 students (78% response rate). How did I summarize? Learn more about my technique, and why. I am going to share the summary of every single response with you. Then, I’m going to summarize differences between perceived strengths and weaknesses of this semester compared to Fall 2018 in person. Then, I’m going to share what these ratings (granted, just one class) can tell us about how to support students’ online learning in large classes. I share this information because it was hard for me to find in Summer 2020. Our university does an excellent job in preparing online instructors, and offered many additional trainings and workshops for faculty to take their classes online. But our online classes are historically designed to be relatively small, and so some of the best practices do not easily scale to large format classes. I consulted with Suzanne LaFleur, Director of Facuty Development at UConn’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, who helped me talk through ideas and provided some great advice that I incorporated. It’s important to note that the way I structured the course only worked because I had substantial TA support. Communication and grading with 350 students would have been impossible if I did not have that kind of support. You can find the full summary of every single positive comment and suggestion for change here. Here are the most common responses, noted by 10 or more students, to the question, “What was the most positive aspect of the way in which this instructor taught this course?” Here are the next most common responses answered by 5-10 students: Here are the most common responses, noted by 5 or more students, to the question, “What can this instructor do to improve teaching effectiveness in the classroom?” (ha – just realized the “in the classroom” part): Interestingly, many of the most positive aspects of the course remained consistent – being engaging/passionate, using personal examples and real world examples, presenting clearly, being nice/caring/friendly, funny/told jokes. Areas for improvement they mentioned in 2018 but less so in 2020: In 2018 many students requested more details on the slides; only 3 mentioned this topic in 2020. More 2018 students described the exams as tricky, though still some did in 2020.

Here are some lessons for online teaching that I take away based on the SETs:

If you are teaching a large online course this Spring, good luck! Feel free to share suggested of what has/has not worked well for you. “What my Fall 2020 teaching evaluations tell us about teaching large online classes first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on January 10, 2021.” * La-de-da. Let’s pretend we didn’t notice how long it’s been since I last posted.

Here is my syllabus for Fall, 2020 in HDFS 1070, a general education lifespan class on individual and family development. The course was fully remote. Here is my syllabus from Fall 2019, fully in person. Here are the things I changed/adjusted to be fully remote:

“Introductory Individual and Family Development: Remote, large section class syllabus first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on January 5, 2021.” I check email a lot – more than I should I am sure. I have colleagues who are skilled at limiting their email checking – only before noon. Only after noon. Never after 9:00 PM. Not on weekends. I fail on all of these accounts, even when I try. In the past, I never, across 365.25 days a year, took a break from email for more than a few hours. What I have done for the past 20+ years, though, is use my vacation message. When I went out of town, whether for work or for a conference (oops, I meant work or vacation), I put my vacation message on. I love that satisfying moment of setting it up. I find the vacation message very liberating, because I can choose whether to reply to someone – they know I am away and so it lowers the expectation of an immediate response. I particularly love that at UConn, if someone emails me from within UConn using their UConn account in Outlook, once they start the email they can see I have a vacation message, and they are, I believe, less likely to send their message. But even when I was at Penn State, I would often, while away, receive messages and then a follow up, never mind, I see you’re away, and I figured it out. Basically, I love the moment I set that vacation message and the corresponding decreasing sense of responsibility to swiftly respond to each message. In the past though, I always continued to check email across every break, even if my vacation message was on. I often didn’t reply, but sometimes I did if it seemed important, or quick. But more critically, if it was an annoying email, or about a problem, even if I didn’t reply, it was in my head. I would be thinking about it, or feeling an increase in stress levels, because that message existed. The summer after my first year as department head, my husband and I took a 4-night vacation to Bermuda to celebrate our 15-year anniversary. It was our first real trip without the kids since they were born. And after much deliberating and stressing about it, I decided not only to turn on the vacation message, but also not to check my work email. I still checked my Gmail account, and so people in the office knew if it was an emergency they could contact me. My vacation message explained I wouldn’t be checking email, and whom to contact instead. I moved my work email icon on my phone off of the first screen so it wasn’t always in front of me. And, for about 5 days, I never checked my work email. Seriously, would you want to be checking work email while here?: Guess what? Everyone survived. Nothing came up that couldn’t wait. And, when I returned I felt a lot more rested and ready to tackle the email and work in general. Last summer our family went to Spain for about a week, and I did the same thing. Again, nothing went terribly wrong, no one ever had to contact me there, and I dealt with everything when I returned. Can’t really tell in the photo, but I was rather relaxed: And most recently, for about 9 days in June, my family was in the UK, and I put up this vacation message: Thank you for your message. I am out of the office and will be doing my best to recharge before returning to the office on June 26th. During this time, I will be using all of my will power not to check my email. If this is an emergency, please contact one of the following: [DETAILS] Otherwise, I will certainly respond to you as soon as I can when I return. In the past, I have used variants of this message, with lines such as “I hope that you also find times to disconnect and recharge this summer.” This trip was a bit longer, but again, nothing burned down in my absence. And, with jet lag, I was up at 5:00 AM my first morning back and had sorted through all of the email by about 7:00 AM, even though of course I didn’t respond to everything in 2 hours. Instead of checking email, I was taking time to really appreciate the scenery, like at this moment after climbing 212 stairs in Bath Abbey (thank goodness for all of my stairs walking at work): If you haven’t ever really, truly disconnected from your email, I highly recommend you find a time to do so this summer. Let me know if you find it as freeing as I do.

“The joy of the vacation message first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on July 2, 2019.” If I convinced you that grant writing matters for many different post-PhD jobs, you may be wondering how in the world you can get grant funding. Trying to get external funding can be a daunting task, particularly for a new faculty member who has never pursued such funding before, and is juggling research, teaching, and service. Even knowing where to apply for funding can be confusing at the start. Most people know about NIH as a potential funding source, but there are many other possible sources that people may not as quickly consider. I wanted to review these sources today – and also discuss the differences between grants and contracts. These sources apply both to faculty, and to research associates in a range of different positions discussed in my recent post.

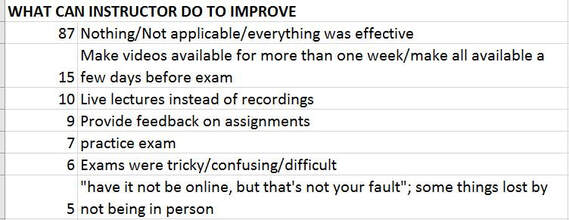

What’s the difference between a grant and a contract? It has taken me some time to determine the difference, but I found this chart from University of Pittsburgh very helpful: [Source: http://www.research.pitt.edu/fcs-basics-federal-contracting#GrantvsContract]

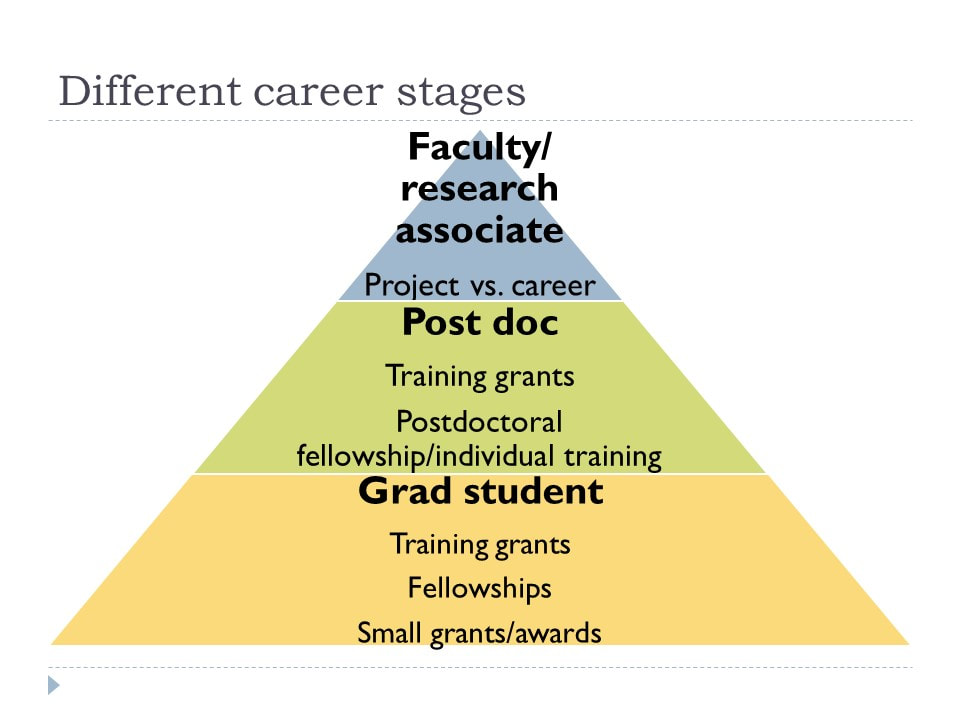

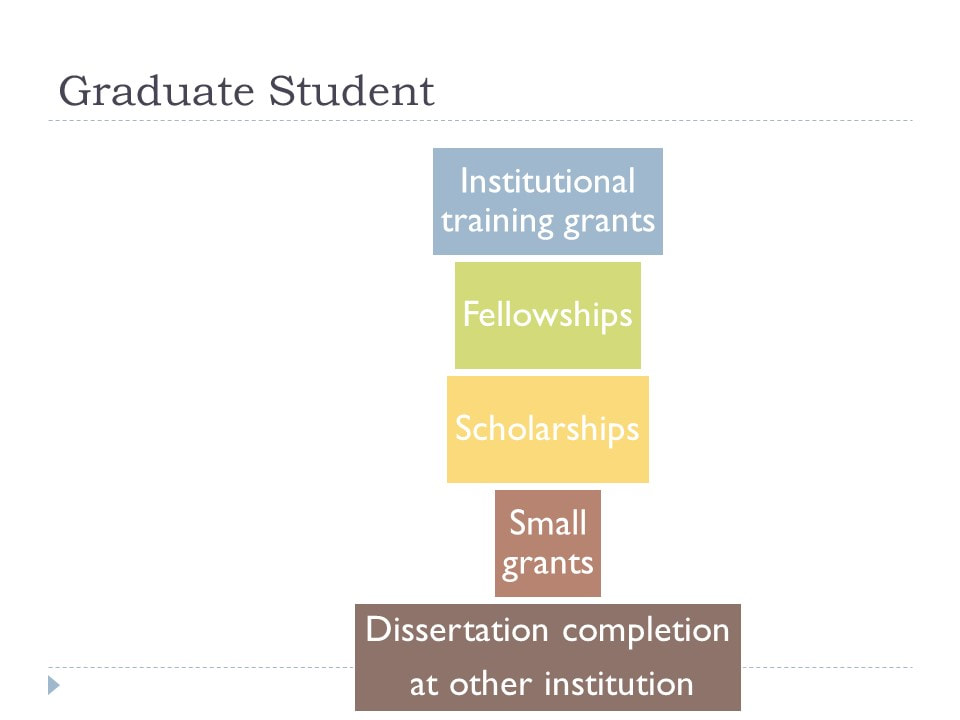

In summary, grants are often investigator-initiated – you develop the research question. Contracts are often agency-initiated – they ask you to answer a specific question they want addressed, such as the efficacy of an existing program, or what are the effects of substance use among military personnel on their families. You have more flexibility and freedom with grants, both in terms of what you pursue, but also the ability to make changes (e.g., new constructs, new measures), less frequent reporting, and fewer restrictions on when you release your findings. “Common sources of external funding for faculty/research associates first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on June 27, 2019.” In my professional development seminar, we have a week on grant writing. Of course, the topic of grant writing could be (and frequently is) a course in itself, so what I cover in 2.5 hours is really only an overview and primer on thinking about grants. Research grants are not only relevant to faculty; they might fit into your career at several different stages. [I got really excited about PowerPoint’s SmartArt feature this past semester] In terms of graduate students, there are a range of grants/fellowships that grad students can apply for, which I’ve covered in an earlier post, though now I have a cool new graphic. There are also different types of postdoctoral funding, which I also covered in an earlier post.

In terms of grants that one might apply for at the faculty/research associate level, there are a range of sources one might pursue for grant funding. I am going to write about this topic separately, soon. First, though, I want to discuss different kinds of PhD-level jobs where either grant writing is part of your expected job responsibilities, or the skills you develop during grant writing are valuable as transferable skills for that position.

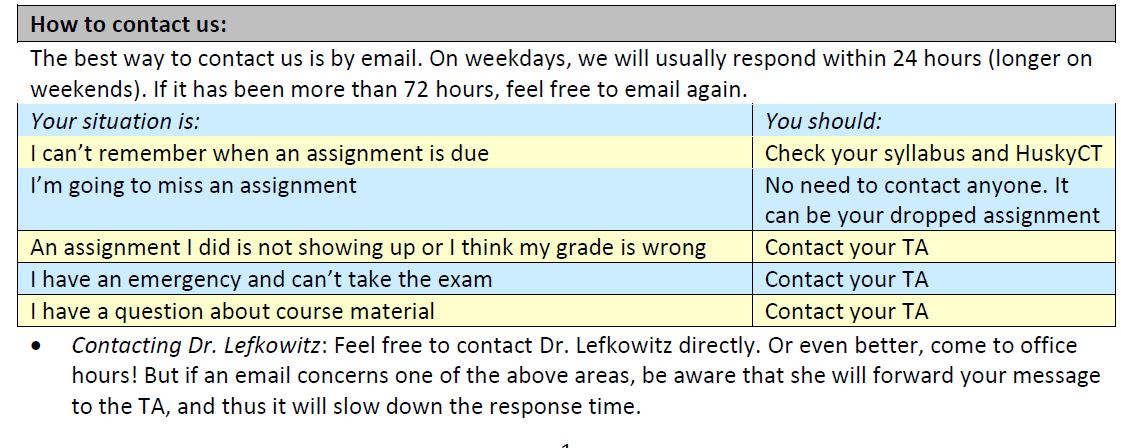

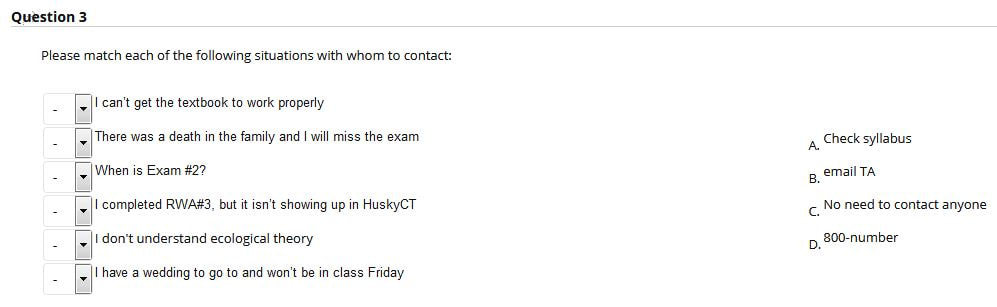

I won’t argue that every job post-PhD requires grant writing skills. However, many different careers benefit from such skills, so getting these experiences early on can be highly marketable. “Jobs where grant-writing matters first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on June 25, 2019.” The last two academic years I taught a large intro course, with 300 and 350 students. The last time I taught a course with 200 students was my first year as an assistant professor – 1998. The last time I had 100 students was 2000. So, I had some new learning to do about how to handle large classes, and also, how to teach large classes in 2019 (well, technically it was 2018). One large management issue with 350 students is emails. I was fortunate to have three TAs each time I taught, so they honestly dealt with the majority of the emails. Even if students emailed me, I would skim the email and assuming it was one that should go to the TA, forward it to that student’s TA (they each had part of the alphabet). How should students know if they should email me or the TA? It’s in the syllabus, of course: This information was my attempt to decrease overall emails and make it as easy as possible for students to know whom to email and when. It’s a challenge in a large course to appear both approachable when needed and not standoffish, but also not have every student email weekly with questions they could answer on their own. Despite these attempts, I received emails from students every single day, at least 90% of the time about topics they should have emailed their TAs (or no one) about. The TAs became very good at screenshotting the syllabus and sending it to students in their replies. Unfortunately, a clear syllabus is not very useful unless students read it. And, it has become very challenging to get students to read the syllabus. There is little incentive, as far as I can tell, especially given how little effort it takes to email the instructor/TA with a question rather than look for the answer in the syllabus. I tried to keep my syllabus as short as possible – it is five pages. Perhaps that seems long, and I have read about the one page syllabus, but note that the one-page syllabus usually has a number of appendices or addendums, at which point you are asking students to read multiple documents. I’d rather have it all in one place. I use bullet points and tables. And multiple colors. Yes, I have a syllabus quiz. It is due one day after the end of add/drop period so that everyone in the course can take it. It is worth points toward their final grade. It is online so they can take it at home, with the syllabus in front of them. They can take it as many times as they would like until they get a score they are satisfied with. Most students did eventually get 100% (84% of them). But 4% never took it, and 8% scored 83% or lower, even with retakes. The most recent time I taught the course, I also put an Easter egg in my syllabus. Any guesses on what percent of the class did the extra credit based on the Easter egg in the syllabus? I’ll wait. 11%. You might wonder, why would I reveal my Easter egg in a blog post? I figure if the students didn’t find it in the actual syllabus for the course they took, they are not going to find it buried in a blog post.

Want to see my whole syllabus? You can find it here. Normally my blog posts provide advice for academia. I’m not sure this post could serve as best practices for getting students to read the syllabus, though, because, as you can see, I have not been particularly successful. I would love to hear what you have done to get students in large classes (any classes?) to read your syllabus. “It’s in the syllabus first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on June 20, 2019.” I am a huge fabric poster convert, and my goal is to convince everyone that their lives will be better if they use fabric posters. I do not have any investments in fabric poster companies, nor do I have affiliate links – I just think you will be happier if you too convert to fabric posters. Here are, in my opinion, the benefits of fabric posters:

So, I convinced you, and now YOU want to make your own fabric poster. But how? The website I have used is Spoonflower, recommended to me by Rose Wesche. Thanks to Mackenzie Wink for figuring out the details of how to use it and helping it get set up in our department. So most of this information comes from them. 1. Create a login 2. Click upload- you will upload a JPEG image of the poster **PLEASE NOTE: THE POSTER MUST BE UPLOADED IN THE CORRECT FORMAT. It must be a JPEG not a PowerPoint or pdf. This link explains how to convert it. 3. If you have to come back to the account before being able to checkout with the order, the poster will be in your 'Design Library' 4. Ensure that settings are correct- a. Centered (the default is a repeated design meaning multiple posters would print repeatedly on the poster like a fabric pattern) b. 48X36 c. Performance Pique fabric d. 1 yard 5. Make sure that the poster looks exactly how you want it in the preview window (make sure you can see the whole thing, etc.). This preview will be exactly how it prints. 6. checkout It’s actually quite straightforward. And I bet once you try it, you will be converted for life. Until we all go to digital interactive posters. “Where I convert you to fabric posters first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on June 18, 2019.”

|

Eva S. Lefkowitz

I write about professional development issues (in HDFS and other areas), and occasionally sexuality research or other work-related topics. Looking for a fellowship?

List of HDFS relevant fellowships, scholarships, and grants Looking for an internship?

List of HDFS-relevant internships Looking for a job?

List of places to search for HDFS-relevant jobs Categories

All

Blogs I Read

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed