I’ve learned over time that the preparation students receive from their instructor in advance of having to track down articles varies widely. Some instructors fully prepare students for this task, particularly in honors seminars. Others, particularly by graduate school, expect students to know how to perform a successful literature review. So, my advice on how to do an effective literature search may be useful for students toward the second half of their undergraduate career, or early in their graduate career.

- Starting with a textbook: If you’re early in the process – let’s say, trying to narrow down a topic for a review paper for a course or your thesis, looking at your textbook for that course, or other courses, can be useful. Textbook writers spend a lot of time tracking down articles on a huge range of topics. You can see what articles the textbook cites, and track down those original sources. For instance, if you're interested in sexual behavior, you can look in the sexual behavior section of your adolescent development textbook and track down the papers that the textbook author cited.

- Review articles: In many areas of research, someone (or multiple someones) has published review articles or meta-analyses. Review articles can be very useful because they summarize a fair bit of past work. However, there is a lot of information in one paper, so you will have to spend a lot more time reading it than an empirical article that summarizes only one study. To find review articles, you can check the titles of articles during your searches for ones that include “meta-analysis" or "review" in the title. The reference list of the review article will help you find other relevant articles (though they obviously will be older than the review article). You can also look at some specific journals that carry review articles, including Psychological Bulletin, Psychological Review, Human Development, and Developmental Review.

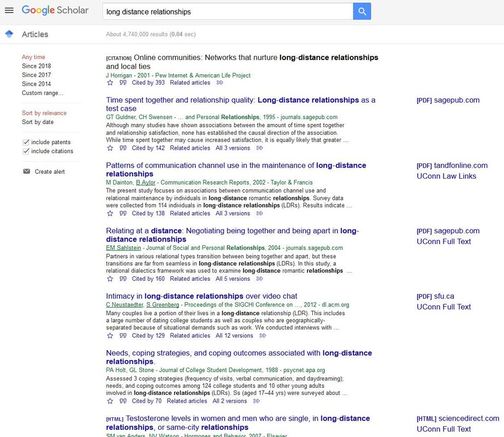

- Searching in databases: Use Psychinfo, Google scholar, or other journal database to find articles on a specific topic. Learning to choose the right search terms can take time. You may need to spend a fair bit of time practicing and trying out a range of different terms before you find the right articles. If a search gives you < 10 articles, you need broader search terms. If it gives you > 1000 articles, you probably need narrower terms. If you’re using google scholar, using quotation marks can be really important. Let’s use an example. We recently wrote a paper on long-distance relationships. Here are some things I could try:

- LONG DISTANCE RELATIONSHIPS: Without quotation marks, there are 4,740,000 results. Obviously that won’t work. Though, when I look at the first page, it is clear that they are likely some of the most relevant ones.

- LONG DISTANCE RELATIONSHIPS: Without quotation marks, there are 4,740,000 results. Obviously that won’t work. Though, when I look at the first page, it is clear that they are likely some of the most relevant ones.

- “LONG DISTANCE RELATIONSHIPS”: If I put it in quotes, it goes down to 6,760. That’s still probably too many for me to search through.

- LIMITS: if you look on the left side of the screen in the screenshot I took, you will see that there are a couple of really quick limits I can set.

- Removing “patents” and “citations” doesn’t help much; it’s now down to 6480

- Years: I have mixed thoughts on limiting searches by year. If I limit to the past 10 years, using a custom range from 2008-2018, it narrows down my results to 4860. That helps, some. And if your instructor or advisor said to only use recent articles, or articles in the past 5 years, or another time-limiting range, then it makes sense to limit that way. But I also fear that emerging scholars are missing a lot of earlier, no less important work by limiting their searches (more on this point later).

- Additional search terms: I can narrow to a specific aspect of long distance relationships. If I add loneliness, I get 1470 matches. College gets me 3340 matches. Alcohol gets me 973. So, I may be able to narrow down some that way.

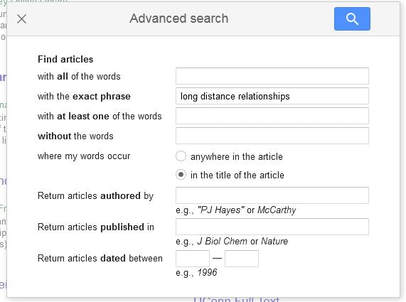

- ADVANCED SEARCHES: Using the advanced search in google scholar, or using more search terms in psychinfo, can be very useful for narrowing down your search. For instance, if I change the search to be only in the title, it quickly narrows to 178 that use “long distance relationships” in the title. That may be a better starting point than the 6480, because those papers are more centrally about long distance relationships than many of the others that have dropped from the results.

- Snowballing: If an article you read cites another article to make a specific point relevant to your interests, look it up. Researchers use this approach a lot.

- Forward searches: This technique is one of my favorites, because to me it feels like detective work. In psychinfo and google scholar, you can find all the articles that cite a specific article. So, if you find a great article on your topic, you can find all the articles published subsequently that refer to the great article. Some may not be relevant to your topic, but many likely will be.

- Don’t stop at first page of results: When you do a search, go beyond the first page. I have had students come to me with a reference list where everything was published in the past 2 years, and some are only tangentially related to their topic. The student often then tells me that s/he couldn't find anything more relevant. But often the issue is that the student didn't look through enough of the results in his/her search. When I do a search, I generally look through every article that comes up. That's why you want your search to be specific enough that it produces < 1000. The most recent research may be great, and you want to include the most recent research, but if you're not going more than 2 years back, you're likely excluding a lot of other great research.

“Good journal article searching habits first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on October 30, 2018.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed