I don’t think I ever read a draft of a paper only once. In the “olden days” I would read students’ drafts in hard copy, and make handwritten corrections/comments. When students handed me a new draft, I would ask for the prior version with my handwritten comments and go back and forth.

Now that I edit in Word using track changes and comments, I noticed that I was reading new drafts and going back and forth to the old draft to see my earlier comments and whether students replied. It contrasts with when I am a blind reviewer on a journal manuscript, and I receive a response to all of my reviewer points, so I can go through the response letter and see how the author responded to my requests.

It felt inefficient, and so I came up with a system that works much better for me. I ask that students follow these guidelines when sending me a previously read draft:

- Turn off track changes

- Go through each suggested edit, and either accept it, or add a comment as to why you didn’t accept it (yes, you can disagree with my suggestions, just explain why)

- Simultaneously you’ll be accepting your edits from the earlier round

- Find any comments that were from an EARLIER round of edits (e.g., I just read it on May 30th, but there are leftover comments from April 27th), and delete those older comments, unless they aren’t resolved (e.g., delete the April 27th comments)

- Turn track changes back on, and go through my comments

- For each comment, either edit the manuscript, or respond to the comment as a new comment (or both)

- Reread the whole paper, and make any additional changes/edits (with track changes still on)

- Send back to me.

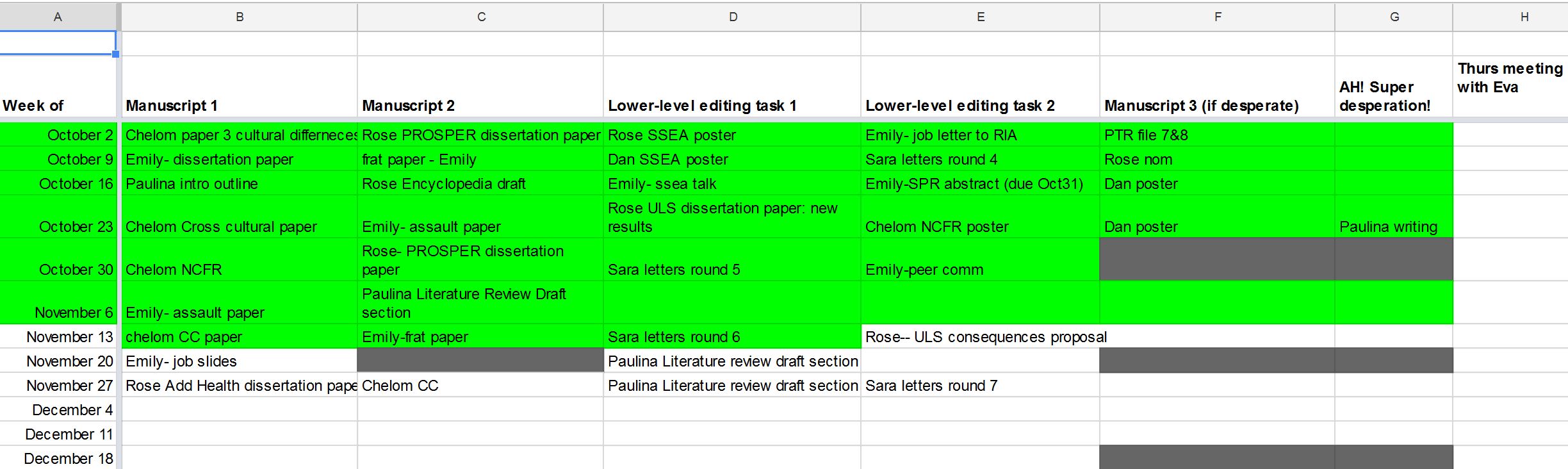

If we are at a point where I don’t feel that I have to read the whole thing, I will highlight the paragraphs I want to reread, or put in a comment on the title page that says “Eva only has to read first paragraph and whole discussion.” This tracking also helps me immensely. When I was younger and editing fewer things, I likely could remember when someone returned something that I only needed to reread discussion that version. But now, with more years behind me, and more frequent co-authored editing, by the time something returns to me, I’ve lost track of where we left off. To put it in perspective, not including first-authored papers, I currently have 5 co-authored submitted papers, and 6 co-authored drafted, so I am reading a lot of drafts in any given month.

I try to follow a similar process when I’m first author – when I send a new draft around, I have gone through and accepted (or not, with a comment) my earlier changes and suggested changes from co-authors, and then I turn on track changes and make new edits in response to comments. I also respond to comments as needed, e.g., if I don’t make a change, or if co-author had a question about something. Hopefully this annotating helps my co-authors as much as it helps me.

“The post How to Edit Co-authored Papers More Efficiently first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on May 31, 2018.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed