The post “Males’ contraceptive attitudes matter more than females’ attitudes in adolescent couples” was first published on Eva Lefkowitz's blog on November 30, 2015.

|

Sara Vasilenko, Derek Kreager, and I recently published a paper in Journal of Research on Adolescence. We used couple data from Add Health to examine how partners’ contraceptive attitudes correlate within dyads over time, and how well male and female partners’ attitudes predict subsequent condom use. Our findings demonstrated that even after controlling for adolescents’ own attitudes, partners’ prior attitudes predicted subsequent attitudes for both male and female adolescents. The association, however, was stronger for female than for male adolescents. In addition, when put in the same model, males’ attitudes but not females’ attitudes predicted couple’s subsequent condom use. These findings suggest that male adolescents may have more power or influence on contraceptive decisions within adolescent relationships.

The post “Males’ contraceptive attitudes matter more than females’ attitudes in adolescent couples” was first published on Eva Lefkowitz's blog on November 30, 2015.

0 Comments

See last year’s discussion of cognition and schools here.

A student presented on the following question: Should knowledge of brain development inform decisions about legal ages and/or public policy? She gave an overview of brain development in adolescence and the impact of pubertal changes on behavior. Then she discussed several topics such as whether the drinking age should be lowered (see this interesting debate in the NY Times); hot vs. cold cognition, and some of the papers by Steinberg on specific court cases and public policy; the role of peer influence, including work by Chein and colleagues; and the policy of graduated driver licensing programs. We talked about the ways in which classrooms and schools do or do not match adolescents’ developmental stage, including both classic and recent work by Eccles and colleagues. Next year I think I want to pull in homeschooling research. If you know of interesting research in this area, let me know. “The post Last semester in Adolescent Development: Cognition & schools 2 first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on November 22, 2015.” Every Spring semester, I lose control right around the end of Spring break/SRCD and then reemerge around May. So hello. Thus, Summer Eva will be catching us up on what we covered in the Spring in Adolescent Development and in Professional Development. (NOTE: I drafted this post in May, but somehow lost control of the blog again in the Spring, so hello. Again). Today, I’m covering the mechanisms of writing a manuscript. We have already reviewed choosing a journal. And for my advice on the specifics of writing, see my intentional writing series. Tailor to the journal (when possible). Something authors often do is write a manuscript, decide where to submit it, and then go back through to make it fit that journal better – add more adolescent development theory if it’s an adolescent journal; add a prevention spin if it’s a prevention journal; shorten it if the word limit is less than the manuscript, etc. If, on the other hand, you can decide on the journal in advance, then you can tailor the manuscript to that journal to begin with, keeping the journal’s focus, criteria, and word limit in account from the beginning. Hourglass shape. [Insert bad joke here about how we all want to obtain an hourglass shape]. I learned this analogy in grad school, and somehow assumed that everyone else did too, but recently learned that it’s not universally taught. So, think of your manuscript/journal article as an hourglass. It starts broad/wide, gets narrower and narrower, and then widens out again. At the start, the introduction starts broad and narrows: it starts with larger/big picture ideas to show how your ideas relate to larger issues. You then move to theory, and then to prior empirical work, before stating your specific hypotheses. Your methods and results are the narrowest because they explain exactly what you did, and what you found. Then your discussion is the opposite of the introduction, because it starts relatively narrow with a summary of your results, moves broader in situating your results in the larger literature, then how your results address theory, and then finally, broader conclusions and implications.

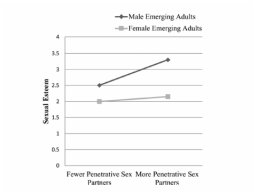

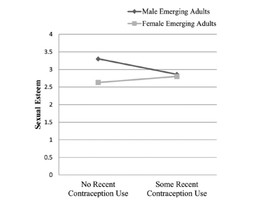

First sentence and abstract. Intentional writing is important for your entire manuscript, but even more so in the first sentence and abstract. Many people will only read your abstract – or will use it to decide whether to keep reading. Be clear, so that if someone only reads the abstract, s/he will know exactly what you did, how, and why. And don’t bore them. Elsewhere I’ve discussed the importance of the first sentence and starting strong: make the reader excited about what you have to say next. First page. Your first page should summarize why your study matters, and what you plan to do (White, 2005). Sometimes authors work so hard to build a case for their study that they forget to start with the summary of the case. As White says, “Too many authors wait until p. 13 to tell the reader whether they have 20 or 10,000 cases.” (2005, p. 792). Not that many readers will make it to page 13 if you don’t tell them why they should bother. Literature review. Unless your paper is actually a literature review, it should not summarize everything that has ever been done before in this area (White, 2005). Choose key citations to make your points, and present all sides of an issue, but do not try for a comprehensive literature review in an empirical paper. Headings. Use them. Discussion. One frequent mistake I see as a reviewer is when authors write paragraph after paragraph interpreting their findings, without situating it within prior literature or theory. A good rule of thumb is to make sure that you have citations in just about every single paragraph in your discussion, and that the citations are not only to your (or your adviser’s) work. By the end of the discussion, readers should have a strong understanding of your contribution to the literature, both in terms of building on prior empirical work, and addressing theoretical questions. “Every sentence matters.” This quote is from my colleague Steve Zarit, one of the most prolific and well cited professors I know. Don’t waste space. Consider the importance of every sentence. First draft. Get it out. Even though every sentence matters, every sentence does not matter in your first draft. Never let a sentence or a paragraph hold you up. Get through the whole paper, even if you have to use tricks like “INSERT SENTENCE ABOUT RATES OF CONDOM USE IN ORAL SEX HERE” or “SAY SOMETHING INTERESTING ABOUT WHY THIS MATTERS HERE.” Get through the whole draft, and then worry about tackling the sticking point details. “The post Mechanics of writing a manuscript first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on November 17, 2015.” Extensive works considers the negative physical and mental health correlates of sexual behavior during adolescence, but less work considers the potential positive role that sexual behavior plays. By the college years, when engagement in sexual behavior is relatively normative, sexual behavior may be associated with positive wellbeing, much as it is in adulthood. In a recently published paper, Megan Maas and I examined how sexual esteem relates to sexual behavior in the University Life Study. We found that sexual esteem was higher for students who had oral sex more frequently, had more oral and penetrative sex partners in the past 3 months, and had spent more semesters during college in romantic relationships, than for their counterparts. There were some interactions with gender. For instance, the association between sexual esteem and number of penetrative sexual partners was stronger for male than for female students. In addition, male students who never used contraception tended to have higher sexual esteem, whereas female students who never used contraception tended to have lower sexual esteem, compared to students who used contraception. These results are cross-sectional, so we cannot know whether having better sexual esteem is associated with engaging in more sexual behaviors, or whether engaging in more sexual behaviors leads to better sexual esteem. However, the results do demonstrate that unmarried sexual behavior after high school is linked with positive wellbeing. On the other hand, results also suggests that men with better sexual esteem might engage in riskier behavior, whereas women with better sexual esteem might be more likely to protect themselves, mirroring earlier findings Meghan Gillen, Cindy Shearer, and I had with body image.

I’m excited that more and more researchers are now approaching the study of adolescent and young adult sexuality from a normative, developmental perspective rather than consistently using a risk frame. Adolescents and young adults do engage in risky sexual behaviors, of course, but we need to understand risky behaviors in light of the positive contributions that sexual behavior provides to wellbeing. “College students’ sexual behaviors are associated with better sexual esteem” first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on November 12. We talked about crowds, based on readings on the topic (see last year’s summary). My students generally felt like the concept of crowds doesn’t translate that well to contemporary adolescents, and that adolescents’ experiences are more flexible and fluid. What do others think?

We discussed some recent research by Besic et al. (2009) that examined whether certain radical peer groups, like Goths and Aesthetics (music, drama, & art high school track, “startling appearance”) are effective defense mechanisms for dealing with inhibition/shyness. Besic and colleagues concluded that adopting the physical appearance of such a radical crowd was not effective, as these adolescents, even when matched to adolescents from other groups on inhibition, were higher in depression and lower in self-esteem. Luckily one of my students this semester uses social network analysis so he could answer detailed questions from classmates about it. We discussed a recent paper by de Castro et al. (2015) that argues for the value of using experimental designs in peer research to disentangle selection and socialization. They present some interesting examples from an online game, Survivor, in which they can manipulate the features of peers and whether the peers are rejecting or not. “The post This week in Adolescent Development: Peers 2 first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on November 8, 2015.” I've written before about starting with a strong and powerful introductory sentence.

This morning I am working on a lit review for a paper, and I came across a strong introductory sentence and thought, let me share all of the strong ones I come across this morning (do you see where I'm headed yet?). I had 24 papers to read through, and found 2 where I thought the first sentence was particularly noteworthy. Many of the others were interchangeable. And I wish I could share some of them here as examples of what not to do. But I'm too nice. So here are the two I liked: In an era when sex is used to sell everything from toothpaste to transmissions, the idea that large minorities of adults might have little or no sexual contact with others seems incongruous to many people. (Donnelly et al., 2001) Over the past decade, a quiet revolution has been occurring in personality psychology, and an age-old scientific problem has recently begun to look tractable. (Goldberg, 1992) |

Eva S. Lefkowitz

I write about professional development issues (in HDFS and other areas), and occasionally sexuality research or other work-related topics. Looking for a fellowship?

List of HDFS relevant fellowships, scholarships, and grants Looking for an internship?

List of HDFS-relevant internships Looking for a job?

List of places to search for HDFS-relevant jobs Categories

All

Blogs I Read

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed