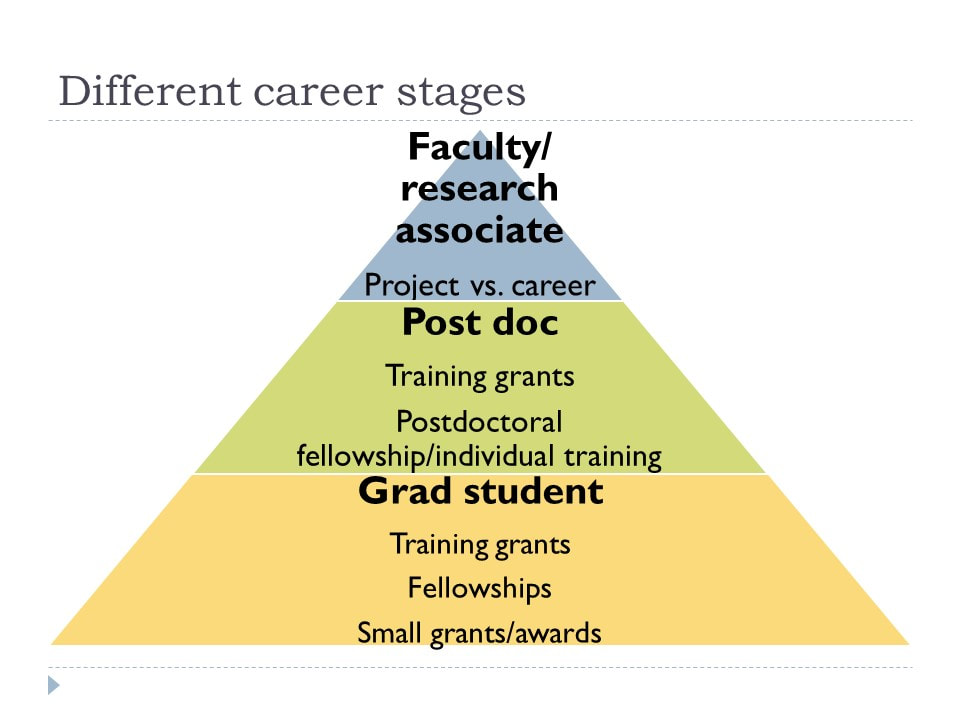

Research grants are not only relevant to faculty; they might fit into your career at several different stages.

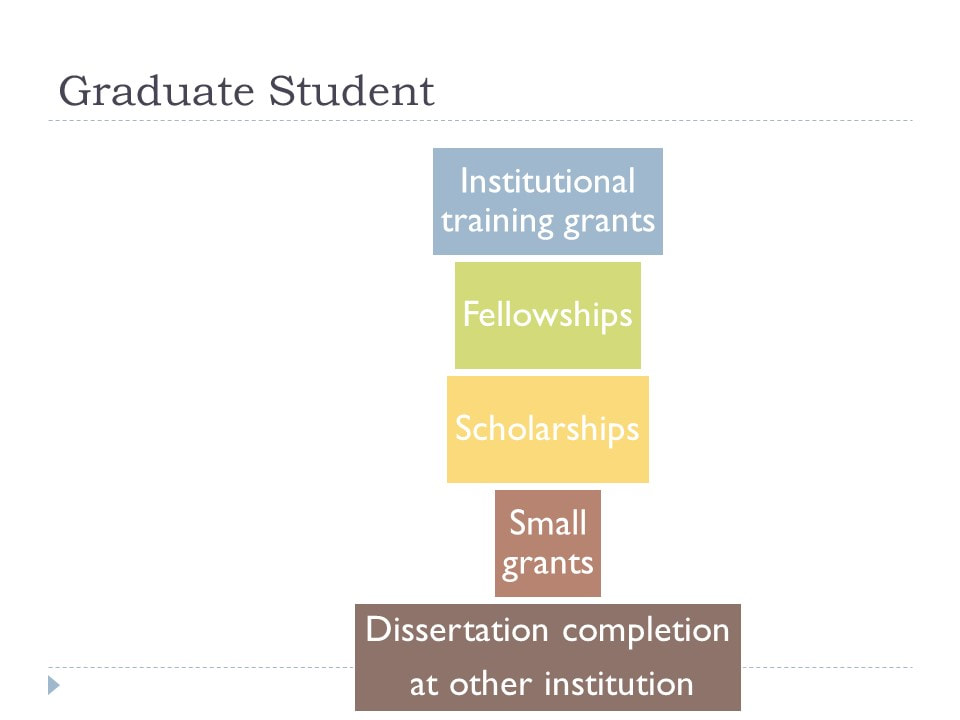

In terms of graduate students, there are a range of grants/fellowships that grad students can apply for, which I’ve covered in an earlier post, though now I have a cool new graphic.

In terms of grants that one might apply for at the faculty/research associate level, there are a range of sources one might pursue for grant funding. I am going to write about this topic separately, soon.

First, though, I want to discuss different kinds of PhD-level jobs where either grant writing is part of your expected job responsibilities, or the skills you develop during grant writing are valuable as transferable skills for that position.

- Tenure-track faculty positions: Probably the most obvious. If you are in a tenure track position, particularly at an R1 university, there is usually an expectation that you will pursue external funding to support your research. At other universities, depending on their research-focus and the type of department you are in, there may or may not be such an expectation. If you are at a very teaching-oriented university, you may never have to pursue external funding. But keep in mind, often there are other reasons you may need to write proposals, such as applying for a Fulbright, or even applying internally for research leave. Having training/experience in grant writing may prepare you for these tasks.

- Faculty in medical schools/soft money faculty: Many faculty at medical schools are expected to bring in their own salaries. They can do so through teaching, research grants (whether their own or time on others’ research grants), and/or clinical hours. Grant writing is an integral part of such faculty members’ positions. I know people who submit multiple proposals to every NIH funding cycle.

- University research positions: University-based research associates and similar non-faculty positions at universities are also often on soft money. They have to bring in their own salary through their own grants or by serving as an investigator on other people’s grants. Grant writing is a critical part of such positions.

- Research institute: Individuals who work as researchers at research institutes often pursue funding to support their salary/time. It will depend on the position, and depend on the institute, but grant writing is often a large proportion of such positions.

- Government and other funding agencies: If you work at NIH or a research foundation that provides grants to others, you may not be pursuing your own external funding. However, positions at such agencies usually involve being on the other end of the process: writing calls for proposals, giving advice to investigators, reviewing proposals, and managing external research grants. Thus, having grant writing experience can be really valuable for obtaining such a position.

- Non-profit organizations/NGO’s: If you work for a non-profit organization, chances are some of their funding comes from pursuing external grants or contracts. Grant writing skills are very valuable for obtaining such a job and for succeeding once you are there.

- Industry-based careers: If you have a job at a for-profit corporation, you may not need to write grant proposals for external funding. However, a student in my seminar this past semester pointed out that often in industry, you need to write proposals to supervisors for ideas you have for projects – you are essentially asking for internal funding for your internal research or idea. Grant writing skills and experience can well prepare you for such job responsibilities.

I won’t argue that every job post-PhD requires grant writing skills. However, many different careers benefit from such skills, so getting these experiences early on can be highly marketable.

“Jobs where grant-writing matters first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on June 25, 2019.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed