Today, at great personal cost to my self-esteem, I read and summarized all written responses from 266 students (78% response rate). How did I summarize? Learn more about my technique, and why.

I am going to share the summary of every single response with you. Then, I’m going to summarize differences between perceived strengths and weaknesses of this semester compared to Fall 2018 in person. Then, I’m going to share what these ratings (granted, just one class) can tell us about how to support students’ online learning in large classes. I share this information because it was hard for me to find in Summer 2020. Our university does an excellent job in preparing online instructors, and offered many additional trainings and workshops for faculty to take their classes online. But our online classes are historically designed to be relatively small, and so some of the best practices do not easily scale to large format classes.

I consulted with Suzanne LaFleur, Director of Facuty Development at UConn’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, who helped me talk through ideas and provided some great advice that I incorporated.

It’s important to note that the way I structured the course only worked because I had substantial TA support. Communication and grading with 350 students would have been impossible if I did not have that kind of support.

You can find the full summary of every single positive comment and suggestion for change here.

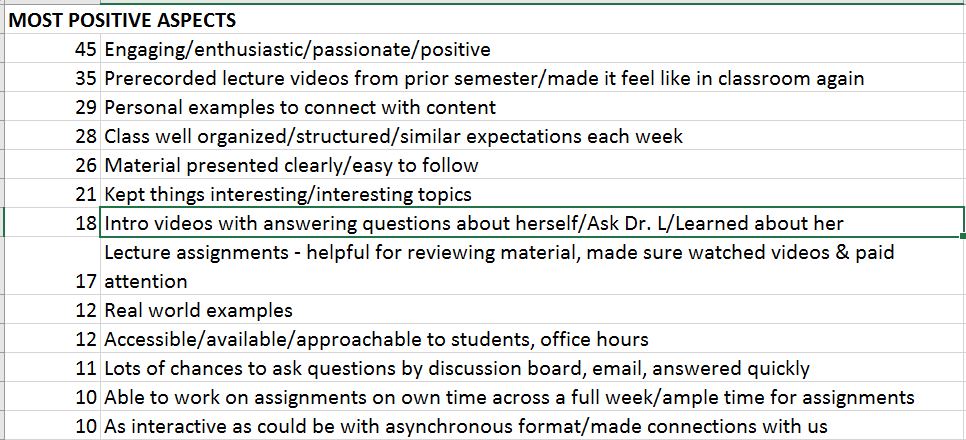

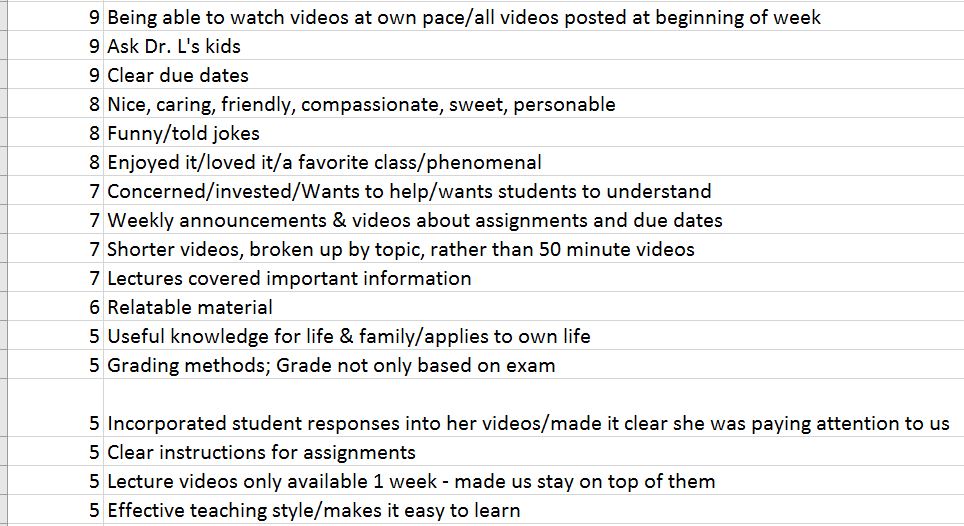

Here are the most common responses, noted by 10 or more students, to the question, “What was the most positive aspect of the way in which this instructor taught this course?”

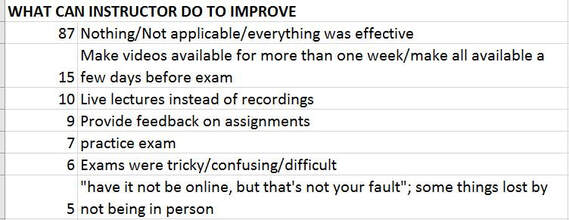

Here are some lessons for online teaching that I take away based on the SETs:

- Your personality/enthusiasm can still come through via video: When I consulted with Suzanne, I told her one of my major concerns was that the thing students tend to like the most about my class is my enthusiasm/passion and attempts to engage students, and I was very concerned it would be lost via remote learning. However, it again was the most common positive response. It was striking that students could still pick up on it without ever being in the same room together.

- Value of prerecorded “live” lectures: I was extremely fortunate that the last time I taught the course, I recorded all of my lectures, and I used those lectures as the basis of my lecture videos in 2020. The balance from student responses was overwhelmingly in favor of prerecording, with students saying that they felt like they were in the classroom because they could hear last year’s students ask questions, and they could imagine being in the classroom. I recognize many instructors will not have this luxury.

- Increase connection with personal examples: in this course I use many personal examples, and (most) students responded positively. They said it helped them understand the material, and that it helped them feel as though they got to know me even though the class was remote. Granted, 3 students also said that I should tell fewer personal stories – and one of those responses was so strongly negatively valenced that it’s what is sticking with me tonight – but 29 specifically mentioned liking the personal anecdotes.

- Be as organized and structured as possible: Much more so than in 2018, students responded to the course being well organized and well structured. Students seemed to appreciate the predictability of knowing what to expect each week, and that the rhythm of assignments and due dates stayed stable.

- Try to talk “to” students: Students appreciated my weekly intro videos where I would go over what to expect in the next week’s videos and review assignments and due dates. In addition, I would answer questions from a discussion board called “Ask Dr. L.” These were sometimes relevant to class or the field, such as questions about my research area, or about careers in HDFS or how I knew I wanted to be a professor. And, sometimes they were completely random, but still fun to answer, such as do you like to collect anything, what is your favorite meal to cook, do you like being the mom of twins, and are there any TV shows you recommend? Students said they really got to know me much as they would with an in person class because of these intro videos. In addition, some students even described the course as “interactive” or that they felt like they made connections with me from the videos. In addition, when we hit the childhood and adolescence units, I added a discussion board called Ask Dr. L’s kids, and they could ask my kids questions. My kids (with bribery) appeared in some of the weekly intro videos and answered questions. My kids were huge troopers on this, although they also embarrassed me some (mostly by being teenagers). Questions included how the pandemic affected them, what it’s like to go to HS socially distanced, how their relationships with their parents have changed since becoming teenagers, what’s it like to have a professor mom (who knows so much about human development), do they have a “twinsense”, please share a fun fact about each other that you use to embarrass each other (the kids got each other’s approval in advance as to what they would share!), and what are your career plans? I have always wanted to bring the kids to my huge lecture hall – both for them to see what it’s like, and to be able to answer students’ questions about children/teens, so this was a fun way to do it.

- Short videos instead of full lectures: I was concerned about posting three 50-minute videos each week. So, I took the previous year’s videos, and chunked them into about 10 videos each week (sometimes a couple more, sometimes a couple less). Several students specifically mentioned that they preferred the shorter videos to classes where there are 50 or 75 minutes videos. The chunking allowed me to cut out unnecessary pieces.

- Small stakes assignments: Even with the shorter segments, I was really concerned about getting students to watch the weekly lecture videos, and knew I wanted to incentive viewing. So, I asked a very short question after each video, which we called Lecture Assignments. There were usually 10 Lecture Assignment questions each week. Often they directly asked about something they learned in the video (but couldn’t answer by simply copying something off the slides; I learned that early on). Sometimes the questions asked them to consider what was covered in the video, and apply it to their own life, or to a character from media/TV. I also used some of these responses in the weekly intro videos (anonymously) so they could learn a bit more about their classmates’ perspectives, too. Students reported that having these questions forced them to watch the videos and pay attention to them.

- Make yourself accessible: I was worried about continuing to be accessible to students, but students described me and the TAs as accessible, available, and approachable. They mentioned appreciating office hours. In fact, I definitely had more students regularly in office hours this semester (via WebEx) than I normally do in person. I had 3 hours each week, and almost never was alone (the TAs though often had no visitors). Sometimes students came to ask clarification on lecture material. Sometimes they asked for exam advice. And sometimes they just wanted to meet me, or were lonely and wanted to chat (one student gave me a tour of her dorm room while in quarantine). There were a couple of students I got to know pretty well. Overall, office hours were my favorite part of the class, and I am so glad I got to know students this way. In addition, I was a broken record about contacting us. In every weekly announcement and in every intro video I said some variation of, “and if you have any questions, don’t forget you can come to office hours, post on the discussion boards, or email us.” We made sure to answer all (M-F) emails and discussion board post within 24 hours, and students noted appreciating that speed.

- Provide weekly due dates and announcements about them: In addition to liking the predictable rhythm of assignments, several students specifically mentioned that they liked that there were assignments due every week. That felt it held them accountable for reading the textbook and watching the videos, and that they were able to stay caught up on the material because of these due dates. They also mentioned that they liked that the videos were available for a full week and thus they could watch them and answer questions on their own time. Also, they appreciated repetition of due dates. I felt like a broken record, putting due dates in every announcement and every intro video, but several students said they liked the frequent reminders.

- How long should videos be available? My videos posted on Monday at 9:00 AM, and came down the next Monday at 8:59 AM. Several students liked that they were available for a limited time (“I really liked the set up of having the lecture videos only available for a week at a time. Especially because this course was entirely online and asynchronous, that provided incentive to learn the material in a timely manner.”), but more students, and the biggest complaint, was that they wanted them available longer. I have mixed feelings about it, because in a face-to-face class, if you aren’t there that hour, you don’t get the lecture. They had 168 hours to watch them! But, also see their point that there ARE videos, so why not give them longer access, even if the assignments are due weekly. Also, normal classes aren’t during the pandemic.

- Recorded vs. live videos: 10 students wished that lectures were live instead of recorded, either regularly, or once a week, or right before the exam. Again, I have mixed feelings, because the logistics of 350 students in a live session is daunting, but I see where they may have appreciated the opportunity to ask questions live. I personally felt less stressed that I didn’t have to do live remote lectures three times a week, and instead used that scheduled time for office hours. But maybe a session right before the exams or another way to do something occasionally would have been effective.

- Providing feedback on assignments: Students wished they had feedback on lecture assignments and group assignments. I completely agree with them of the value in getting this feedback, and believe it’s better pedagogy to provide feedback. I just don’t know how we could have managed it with 350 students. The TAs and I came up with straightforward rubrics for grading very quickly. The TAs had supporting notes for themselves if there was ever a request for why a student lost points. But to give feedback to 350 students a week on 10 questions each would have been infeasible.

- Providing feedback on exams: Teaching a large class, I try to guard my exams – even though I recognize the challenges of doing so with online exams. When the class is in person, I invite students to office hours, share hard copies of the exams for them to look at, and talk them through the ones they got wrong. I couldn’t come up with a similar format for the remote version, but again, I agree with students they would have learned more if I did. I did go over in the prep for the next exams, the topics that students on average struggled with the most on prior exams, and some students mentioned appreciating that review.

- Group assignments: 46% of my class were first year students. I felt a sense of loss for them not to get to meet/know each other, and wanted to address that. In an in person semester, I have them do weekly in class assignments in groups of 3 with the person sitting next to them. Fall semester, I assigned groups at the start of the semester of 8-9, and asked them to use the scheduled class time to meet and go over assignments. These groups caused me and the TAs more headaches than anything else. Even though the class had a designated meeting time, there were complaints from students that they couldn’t meet at that time – it didn’t seem like a valid complaint because they signed up for a class at a certain time, but it was an issue raised in the online environment. The student feedback was mixed. You can’t see it in the responses I shared, but then I discovered that some students answered the question about discussion sections in terms of their groups. More students described them as helpful for learning and/or interacting/getting to know classmates than said they weren’t helpful. So, it’s unclear whether it was worth the headache for the TAs and I, or not. If I did it again, I might make it more mandatory that they show up at the exact time required, and have the TAs drop in on group sessions to answer questions, make sure they were actually there, etc. I had been wary of that type of policing, but in retrospect, it may have actually made less work for us in the end, and made it clear to the groups that they had to be there.

If you are teaching a large online course this Spring, good luck! Feel free to share suggested of what has/has not worked well for you.

“What my Fall 2020 teaching evaluations tell us about teaching large online classes first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on January 10, 2021.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed