These sources apply both to faculty, and to research associates in a range of different positions discussed in my recent post.

- Government agencies: These are often the ones that people think of when they think about pursuing external grants, and include some of the same ones you might pursue during graduate school or for a post doc, such as NIH, NSF, IES, NIJ, CDC, ACYF, USDA, FDA, DoD, and military branches. One challenge with funding from these federal agencies is they sometimes have restrictions on citizenship status.

- State agencies: obviously which state agencies fund research varies by the state you live in. Several of my UConn HDFS colleagues have funding from CT state agencies, and it was not as frequent among my Penn State colleagues. I don’t know if this difference indicates different opportunities in the states, or different preferences among the faculty. But, sources in CT, as an example, include:

- Department of Administrative Services/The Office for Workforce Competitiveness

- Department of Children & Families

- Department of Economic and Community Affairs

- Department of Education and Education Connection

- Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services

- Department of Social Services

- Judicial Branch

- Office of Policy and Management

- Foundations and agencies: Funding from foundations and agencies can be very different from funding from government, and in particular, federal agencies. Federal agencies almost always have specific forms to complete and specific deadlines for when you apply. Some foundations have similar procedures, but others work more one-on-one with potential grantees. More so than with federal agencies, knowing someone personally can often help with foundation funding. Sometimes, you cannot apply for foundation funding unless invited. Here are some examples of foundations that are often relevant to HDFS faculty and alumni:

- American Cancer Association

- American Heart Association

- American Psychological Foundation

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

- Foundation for Child Development

- Kaiser Family Foundation

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

- Spencer Foundation

- Social Science Research Council

- Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues

- Templeton Foundation

- WT Grant Foundation

- Community-based agencies: These tend to be smaller agencies than the foundations listed above, and are often doing more direct translational and applied research than theory testing. Often they will partner with local researchers to address a very specific question such as to assess efficacy of a particular intervention, to do a needs assessment, or to develop a new prevention program.

- Industry funding: Funding from companies/corporations is quite common in some areas of academia, such as in engineering. It tends to be less common in HDFS and other social/behavioral science programs. However, there are times when HDFS faculty may receive industry funding, for instance, from educational materials companies, from companies that develop health-related apps, or from food industries for nutrition researchers.

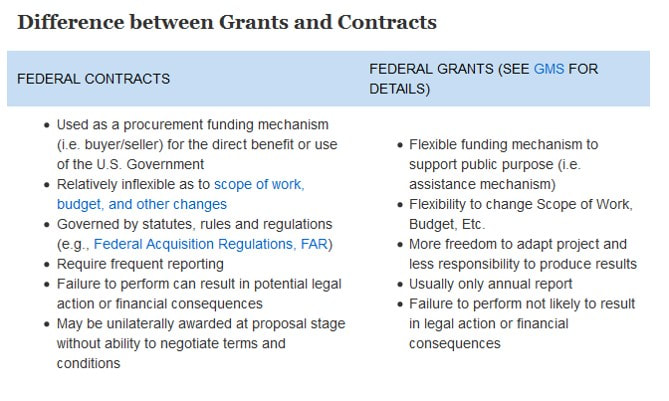

What’s the difference between a grant and a contract? It has taken me some time to determine the difference, but I found this chart from University of Pittsburgh very helpful:

In summary, grants are often investigator-initiated – you develop the research question. Contracts are often agency-initiated – they ask you to answer a specific question they want addressed, such as the efficacy of an existing program, or what are the effects of substance use among military personnel on their families. You have more flexibility and freedom with grants, both in terms of what you pursue, but also the ability to make changes (e.g., new constructs, new measures), less frequent reporting, and fewer restrictions on when you release your findings.

“Common sources of external funding for faculty/research associates first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on June 27, 2019.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed