Profhacker has a great post about live tweeting conferences. The best tips I take from that post, and others I have read, are:

In the audience:

Be respectful. You may disagree with the presenter, and there are ways to do that politely. But the 140 character maximum is quite limiting, and subtlety can be lost with brevity. Err on the side of respect.

Consider people who are not attending the conference. You likely have more followers not attending than attending the conference, and that’s certainly true for the session. Make sure your tweets make sense for people not sitting in the room.

Don’t overtweet. When someone in my feed is at a conference and is tweeting minute-by-minute, I tend to get overwhelmed and wish I could turn them off. It may be okay for one session you’re particularly excited about, but not 8 hours a day for 3 days.

Clearly attribute. Maybe no one has been brought up on charges for plagiarism on twitter. But make sure that if you are directly quoting, you provide quotation marks, and that even if not quoting, you acknowledge the speaker either by username, or if not on twitter, by full name.

First character matters. It’s common for people to begin a tweet with someone else’s username, as in: “@ClaireKampDush explains her strategy for being a productive writer pre-tenure: https://u.osu.edu/adventuresinhdfs/2014/03/06/work-and-family-and-one-night-a-week/ “. Did you know when you start a tweet with a username, only people who follow you AND the other person will see it in their feed? Profhacker recommends starting the tweet with a period (.) beforehand, so all of your followers can see the tweet.

Hashtag. If you want people beyond your followers to read your tweets, use the conference hashtag.

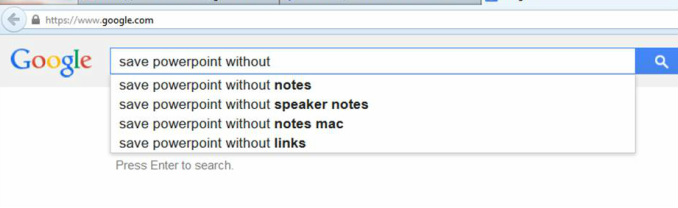

Easily use the conference hashtag. Typing a hashtag each time is awkward. Profhacker recommends text expansion, which could work for you. If you’re lower tech, simply create text and copy it, so you can paste it straight in each time. You can create one simply for the conference (#SRA2014), or if live tweeting a particular talk, you can include the name of a presenter as well, including the . at the front (.@MimiArbeit #SRA2014). Then for each tweet, simply paste it in at the start.

Type quietly!

Think about your prior and subsequent tweets. Twitter is a very public forum (unless you have your account set to private). If you are live tweeting with a conference hashtag, other conference attendees are likely to check out your twitter account. Graduate students in particular need to think about impression management (though of course everyone should think about it). Don’t have your tweet right before the session read something like, “Didn’t think I could drink that many margaritas and still make it to an 8:30 talk! #multitasking”).

As a presenter:

Provide your username on your slides. If someone live tweets your talk, s/he can attribute it to you easily if you tell them how.

Post a tweet right before you present, with, if you create one, a hashtag for your session.

Try to respond to tweets after you present.

“The post Live tweeting conferences first appeared on Eva Lefkowitz’s blog on March 19, 2014.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed